Pop singer Ciara has reportedly been working hard at the gym to correct her abdominal muscle separation, called a diastasis, after the birth of her second child. And she says its working, giving motivation to a dedicated following of moms everywhere. But the question of ‘will exercise work for this condition’ is far from settled. Don’t get me wrong – like most plastic surgeons I’m not fond of taking patients to the operating room for conditions that they could correct on their own with a gym membership. There’s no substitute for exercise, but I have doubts about its effectiveness for diastasis. Here’s why:

Why I doubt that exercise corrects diastasis

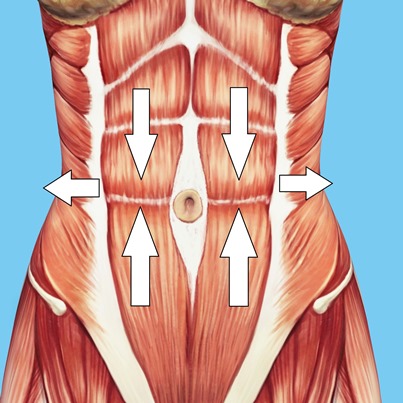

Repair of rectus diastasis (pronounced DYE-uh-STAY-sis) is a routine part of most tummy tucks, so I see this daily in my practice with so many mommy makeovers. The rectus muscles are like a pair of straps that go from the bottom of the rib cage to the pubic bone, with a vertical direction of contraction like you do with sit-ups. Pregnancy often pushes the muscles apart as the uterus expands, resulting in a gap between the muscles comprised only of connective tissue. Sometimes the gap closes on its own over a few months after delivery. This raises the first controversy: How would you know if the separation self-corrected or was the result of your exercise program?

My understanding of how the abdominal muscle function suggests that exercise is more likely to make diastasis worse rather than better. By definition, a rectus diastasis is a horizontal separation, but the muscles contract vertically; their direction of pull is perpendicular to the gap. Lateral to the rectus muscles, the abdominal wall is made of three overlapping muscles: deepest is the transversus abdominis, then the internal oblique, with the external oblique the most superficial. These muscles pull laterally and/or obliquely, away from the midline. It’s a simple fact of anatomy that this direction of contraction pulls the rectus muscles farther apart, not closer together.

Nevertheless, various exercise programs have been put forth, most notably the Tupler Technique®, a regimen of exercise and splinting developed by Julie Tupler, RN, a Certified Childbirth Educator and Certified Personal Trainer. Others have been proposed, generally consisting of a combination of abdominal crunches or drawing-in exercises.

If you have been following my posts you know that I keep an open mind on questions like this, so I looked into the physical therapy literature to see if there was anything I might not have considered. Unfortunately there’s not much to go on; one recent analysis from Australia noted that “papers reviewed were of poor quality as there is very little high-quality literature on the subject” and concluded that exercise regimens “may or may not help.”[i] Another study, using ultrasound to measure the gap, concluded that crunches help but drawing-in exercises were ineffective.[ii] Then there is the view that crunches make it worse, by increasing pressure in the abdomen, pushing up through the gap.

So if you have a diastasis, it might get better on its own, it might get better with exercise (or you could make it worse), but the one thing that we know is effective is a tummy tuck. Even if you can’t fix it with exercise, you will have at least gotten yourself in the best shape you can and your tummy tuck will do the rest.

[i] Benjamin DR, van de Water AT, Peiris CL. Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal and postnatal periods: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2014 Mar;100(1):1-8.

[ii] Sancho MF, Pascoal AG, Mota P, Bø K. Abdominal exercises affect inter-rectus distance in postpartum women: a two-dimensional ultrasound study. Physiotherapy. 2015 Sep;101(3):286-91.